While expanding globally sounds great, it’s not as easy as it seems. Global leaders are challenged with effectively leading teams made up of many different backgrounds, all of which have varying cultural expectations.

Not only do people have expectations for how they should perform work themselves, but they have ingrained beliefs about how a leader should manage a team. And these beliefs differ from society to society.

Luckily, there are two internationally recognized studies that have been published specifically to help global leaders understand cultural differences and be as effective as possible when managing global teams. They are Hofstede’s 6 cultural dimensions and Trompenaars’ 7 cultural dimensions.

We interviewed Gigi de Groot, Senior Consultant at Move Management and previous CEO for itim international (now Hofstede Insights), to discuss the challenges that global leaders face when it comes to different cultural dimensions and how to overcome them in order to provide the most well-rounded leadership possible.

Hofstede’s 6 and Trompenaars’ 7 Cultural Dimensions

Psychologist Dr. Geert Hofstede published his model of cultural dimensions in the 1970s. In his research, he studied IBM employees across 50 different countries. The purpose was to identify cultural differences from one country to another and discern patterns that could help maximize productivity in lieu of team members with highly different cultural distinctions.

A few decades later, management consultants Fons Trompenaars and Charles Hampden-Turner published their study in 1993. They studied the preferences and values of 46,000 managers across 40 countries and found that people across cultures differ in specific, often predictable ways. This is because people who are raised in the same culture are taught similar values and societal norms from a young age, and these values become ingrained like a cultural footprint on one’s psyche.

Let’s take a look at each study from a high-level perspective.

Hofstede’s 6 Cultural Dimensions

- Power Distance Index (high versus low): The degree of inequality that exists between people with and without power in an organization.

- Individualism versus collectivism: The strength of ties that people have to their community.

- Masculinity versus femininity: Masculinity represents a preference in society for achievement, heroism, assertiveness and material success. Its opposite, femininity, stands for a preference for relationships, modesty, caring for the weak and quality of life.

- Uncertainty Avoidance Index (strong versus weak): How well people can cope with anxiety throughout their day-to-day and overall life.

- Long- versus short-term orientation: The time horizon people in a society display. Long-term orientation refers to a more pragmatic approach to goals, whereas short-term orientation places a high emphasis on quick results.

- Indulgence versus restraint: The values placed on enjoying life and having fun versus suppressing gratification and regulating conduct, i.e. looser versus stricter social norms.

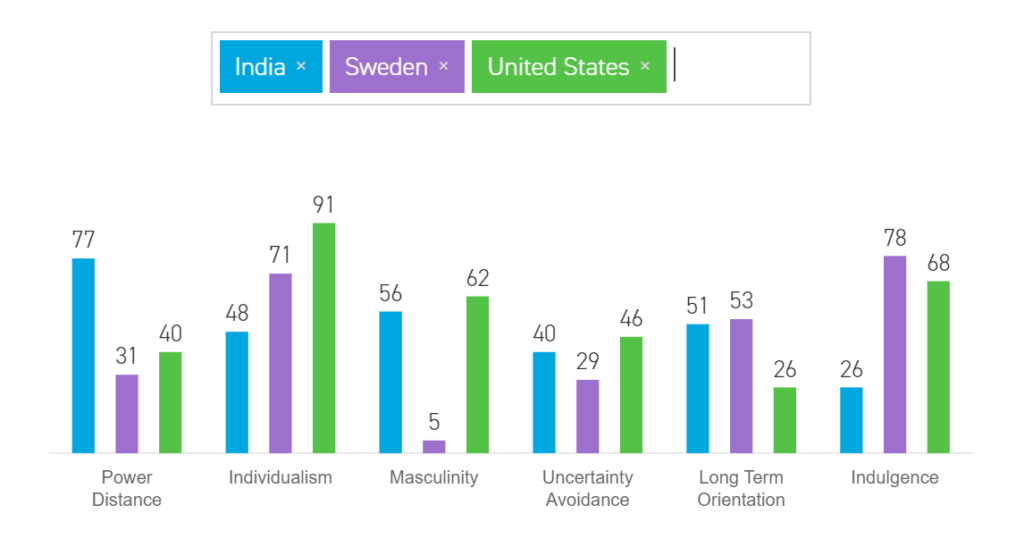

Hofstede Insights has a great, interactive 6‑dimensions model on their website, making it easy to compare countries and their cultural dimensions:

Trompenaars’ 7 Cultural Dimensions

- Universalism versus particularism: Placing value on a set of predetermined rules to determine outcomes versus determining actions based on specific circumstances at that moment.

- Individualism versus communitarianism: The values placed on personal versus communal achievements.

- Specific versus diffuse: How people separate work and personal lives and, consequently, if inter-work relationships are viewed as vital to work objectives.

- Neutral versus emotional: How people express their emotions.

- Achievement versus ascription: The importance placed on work status.

- Sequential time versus synchronous time: Whether a value is placed on sequential events (working on one project at a time in order of due date) or if time periods are viewed as overlapping (working on several projects at once).

- Internal direction versus outer direction: How people relate to their environment (i.e. does the environment control them or do they control their environment).

Which Model is Better?

According to Gigi de Groot, whatever model you use, both can be effective if used to the best of their ability.

“Understanding the models means you are able to see in what way the combination of the dimensions can explain the differences between certain cultures —that is what global leaders truly need to be able to do. It’s the variety of the different combinations of the dimensions that give the models a depth and go beyond stereotyping.”

Gigi de Groot

Interlocking and combining the dimensions are what makes the models so powerful. In order to get the most out of both studies, it’s crucial to mix and match the ideas and analyze them from all angles.

De Groot doesn’t hold a preference for one model or the other. She states the importance of using the tools at your disposal to learn everything you can to make your role as a global leader better.

How a Global Leader Can Put These Models To Use

Let’s run through an example of how to effectively use Hofstede’s cultural dimensions.

The U.S. and the Netherlands both have a low Power Distance Index (PDI). This means that both countries value shared power, or less of a hierarchical distribution of power, within an organization.

However, the U.S. is a more masculine society, meaning that the roles and expected behaviors between men and women rarely overlap and men are expected to portray assertive behavior. Whereas the Netherlands is a more feminine society wherein male and female roles often overlap, and modesty and cooperation amongst peers are valued higher.

In this situation, how can a global leader make everybody work well together?

According to de Groot, the leader needs to focus on multicultural competence or being culturally sensitive and intelligent, in order to successfully navigate this situation. Understanding the theories will help you understand how to use the model as a tool to analyze specific situations and adapt behavior accordingly.

The first step is observation. Be curious about behaviors and allow yourself to be fascinated, rather than distressed, by differences. Then, think about how you can apply the models to your circumstance. What works well for a team member from the U.S. may have the opposite effect on a Dutch employee.

Learn from the research and apply solutions based on pragmatic inferences.

How a Global Leader Motivates People from Different Cultural Dimensions

In our U.S. and Dutch comparison, if you want to push an American to achieve an objective, you’ll need to set challenging goals. Americans more often than not will strive to not only reach but surpass these set goals.

The Dutch, however, will gladly accept the challenging goals at the beginning of the year. But as the year progresses things will change, and therefore the goal needs to be changed as well. In their view the goal needs to be discussed once more, and possibly adjusted to fit the new circumstances if it turns out that the old goal is not reachable anymore. It’s less about the challenge and more about the group involvement.

The key to managing and motivating people from different cultural dimensions is to be sensitive to the fact that everybody will do things differently and to take the time to understand why they do them differently.

How a Global Leader Can Set Common Priorities and Goals That a Culturally Different Global Team Can Collectively Strive For

This is possible and global leaders should absolutely set common goals. Everybody, no matter what culture they are from, needs clear goals that outline objectives to strive for.

However, it’s important to be aware that, while the goals may be the same, the way you support your team members should be different.

Let’s imagine that the goal is to produce a website about global leadership and each team member is from different cultures. The most difficult task for a leader is figuring out how to motivate each individual team member to meet a common goal.

This is where understanding cultural differences and utilizing both models of cultural dimensions becomes important. One team member may want to get started right away, works better alone, and needs to be constantly challenged with new, somewhat spontaneous projects. Whereas other team members may work better in a group, need a detailed project plan, and prefer a set timeline to work at peak performance.

By understanding these differences ahead of time, you can lead your team to hit common goals while undertaking contrasting journeys to reach them.

How Global Leaders Mediate Conflict Arising Between Team Members

Firstly, a global leader needs to understand what their own preferences are, both as an individual and through a societal lens. Are you a leader that likes to confront issues right away, or are you more of a pleaser who handles things at a slower pace?

Your own preferences will often steer what type of solutions you lean towards. If you don’t understand yourself in this way, it will make it even harder to understand your team members’ cultural differences. The most effective leaders are in touch with their individual and cultural sensitivities before attempting to mediate conflict within a team.

However, there are certain situations that prove more difficult than others. For example, if there is one culture more numerous than others in a global team, that culture, based on pure number dominance, can unintentionally set the tone for how things are going to be done. This can become an issue if the culturally dominant team members decide that their way is better than any other, effectively leaving a blind spot for solutions outside of this peripheral view.

As a global leader, it’s important to keep these conditions in check and to ensure the company’s cultural mindset as inclusive and open-minded as possible.

The Specific Challenges of Remote Working Teams

“It’s difficult to build relationships when working remotely when you can’t meet in person. It takes a longer time to build up that personal relationship that breeds productivity. Therefore, it is crucial to invest time in socializing at a distance. ”

Gigi de Groot

According to de Groot, the main challenge of working remotely with global members is building relationships. If not enough time is spent building up a relationship, you can’t build trust, and trust helps us be open about feedback, address challenging issues, make decisions and ultimately, boost productivity.

In collectivistic cultures, the primary focus is on relationships. Only once a relationship has been established beyond the status of colleagues can true work begin. However, some cultures are individualistic and don’t feel the need to connect with other team members in order to work well together.

Let’s use India and Sweden as an example, where the leader is from Sweden. India is a collectivistic culture and Sweden is individualistic. The leader from Sweden wants to get started on tasks right away without any introductions, which makes the person from India feel uncomfortable, as they want to get to know the person behind the voice to be able to work on a task together.

That is extremely difficult when working remotely and is especially challenging for leaders who are often pressured to never waste time and be as efficient as possible. However, by minimizing social time with the team member from India, by for example getting down to business on a Skype-call immediately, a leader may be handicapping their Indian employee who won’t be able to perform as well, because they skipped this crucial cultural step of investing time in relationship building.

De Groot advises that leaders invest time in a team at conception before a project kicks off. If possible, meet in person, and if not, do it virtually. It’s important for leaders to understand that by investing time in the relationship upfront, they will get a higher return on the quality of work, effectively reducing time wasted on feedback and revisions down the line.

Growing as a Global Leader

Global business is on the rise and, therefore, so is the need for effective global leaders. In order to be the most competent global leader, you need to first and foremost keep an open mind. This position is challenging, and educating yourself by using the available tools will boost productivity, reduce stress, and create a dynamic, safe and rewarding team environment.

If you’re curious to know more about global leadership and how to become the best global leader you can be, sign up for eurac’s weekly articles on everything about global leadership.